Ethiopian Teff: The Ancient Grain Shaping Culture, Nutrition, and Economy

1. Historical and Cultural Significance

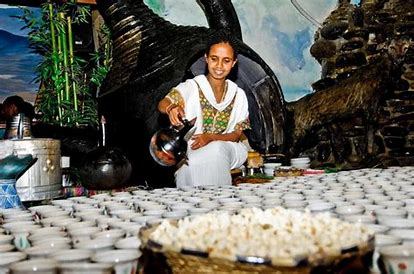

Teff (Eragrostis tef), the world’s smallest grain, has been cultivated in Ethiopia for over 6,000 years, with domestication traced to 4000–1000 BC in the Ethiopian Highlands. Its name derives from the Amharic word “teffa,” meaning “lost,” reflecting its tiny size (1 mm in diameter). As the cornerstone of Ethiopian cuisine, teff is the primary ingredient in injera, a sourdough flatbread consumed daily by over 50 million Ethiopians. Beyond sustenance, teff is deeply woven into Ethiopia’s cultural identity, symbolizing heritage and community.

2. Nutritional Powerhouse

Teff’s nutritional profile rivals that of quinoa and other superfoods. It is gluten-free and rich in essential amino acids (especially lysine), fiber, calcium, iron, and polyphenols. A single serving provides 200–600 kcal daily, making it a critical energy source in both rural and urban areas. Its slow-digesting carbohydrates and high mineral content have fueled its global appeal among health-conscious consumers and those with gluten intolerance.

3. Economic Backbone and Challenges

Teff is Ethiopia’s second-largest cash crop after coffee, generating ~$500 million annually for smallholder farmers. Approximately 6.5 million farmers cultivate teff on 20% of Ethiopia’s arable land, primarily in the Amhara and Oromia regions, which contributes 85% of national production. Despite its economic importance, teff faces systemic challenges:

Low Yields: Average yields stagnate at ~2 tons/ha due to outdated farming practices and susceptibility to lodging (stem bending) .

Export Restrictions: To safeguard domestic food security, Ethiopia banned raw teff exports in 2006, though processed injera is exported to diaspora communities.

Research Gaps: As an “orphan crop,” teff receives limited global research investment compared to wheat or maize, hindering productivity improvements.

4. Agricultural Practices and Innovations

Teff thrives in diverse climates, from drought-prone lowlands to waterlogged highlands, thanks to its C4 photosynthesis and shallow root system. Traditional broadcast sowing is labor-intensive and inefficient, but recent trials of row planting and improved varieties (e.g., Dagim, Quncho) have boosted yields by 8–25%. For example, the Dursi variety achieved 2,761 kg/ha in trials, outperforming local strains. Mechanization and partnerships with organizations like the Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA) aim to modernize farming practices.

5. Global Potential and Future Prospects

Teff’s global demand is rising by 7–10% annually, driven by its gluten-free appeal and nutritional benefits. Countries like the U.S., Australia, and India now cultivate teff, though Ethiopia retains 90% of global production. To capitalize on this trend, Ethiopia partially lifted export bans in 2015, licensing 48 commercial farms to prioritize value-added products like flour and pre-packaged injera. However, scaling production requires addressing:

Infrastructure Gaps: Limited mechanization and post-harvest losses.

Policy Reforms: Balancing domestic food security with export opportunities.

Research Investment: Genome sequencing and breeding programs aim to develop high-yield, lodging-resistant varieties.

Conclusion: Teff as a Catalyst for Sustainable Development

Teff embodies Ethiopia’s agrarian legacy while offering solutions to modern challenges like malnutrition and climate resilience. By bridging traditional knowledge with innovation, Ethiopia can position teff as a global superfood, empowering farmers and enhancing food security. As the world embraces ancient grains, teff stands poised to transform from a regional staple into a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture.

“Teff is not just a grain—it is the soul of Ethiopia’s fields and the promise of its future.”

Explore Further: For detailed insights into teff’s agronomy, economic impact, and cultural role, refer to Ethiopian Teff Production Dynamics and Teff Farming Challenges.

Comments

Post a Comment